Jason Heppenstall – original founder of The Olive Press, back in 2006 – revisits Órgiva and reports on its major changes….

IT HAS always been a magnet for misfits and square pegs, but with the arrival of big supermarkets, better facilities and cleaner streets, are residents right to fear that gentrification will erase Órgiva’s tousled charm? The burning question again, is Órgiva being gentrified?

Why did the sheep move to Órgiva? Because he’d heard it wasn’t a baaad place to live. Okay, sorry, but that’s what you get when you ask AI to tell you a joke about Granada’s finest alternative enclave. For those who haven’t ever visited, Órgiva is a small town nestled between two mountain ranges at the western end of a broad valley. Once a thriving mining settlement, in recent decades it has become a mecca for artists, healers and spiritual seekers, with people coming from far and wide to enjoy its easy charms and to pursue a more chilled lifestyle.

It’s said that in Órgiva, you are never more than six feet away from a yoga teacher – it’s simply that kind of place. But now, there’s a new vibe in town, and the spectre of gentrification has furrowed the brow of many an Órgivan. The once down-at-heel ‘calles’ and ‘plazas’ – beloved of stray dogs, buskers and panhandlers – have undergone a facelift. Meanwhile, new-build developments, combined with improvements to infrastructure and leisure facilities, have dragged the town into the 21st century.

The ’G’ word

It’s a horrible word, isn’t it. Mention the ‘G’ word and one is immediately put in mind of hipsters in ironically named delis, of microbreweries selling overpriced beer, and of trendy boutiques selling urban kitsch at inflated prices. It’s a process of sterilisation in which the living soul of a neighbourhood is exorcised to make way for a new class of hip, urban professionals. Take one vibrant, noisy, and usually grimy locale, and jet wash away all the undesirable elements to make way for insipid commerce, cultural blandness, and rising property prices.

In his book, ‘How to Kill a City‘, American author, Peter Moskowitz, argues that gentrification erases local character and replaces it with bland uniformity. “With every new beige condo building and every new coffee shop that has the exact same aesthetic and sells virtually the same products, cities begin to feel less dynamic, less hopeful, less inspirational to their residents.” The coffee is the same, but it’s served by a guy dripping with beard butter, and it costs three times the price.

Not everyone thinks this is a bad thing. Many point out that cleaner streets, reduced crime and revitalised urban centres lead to improved economic growth. Would you rather bring up a child in a grimy and dangerous neighbourhood, or a clean, safe and ‘bland’ one, they ask, rhetorically. Yet those who rail against gentrification say that the focus on aesthetics comes at the loss of soul. How, they ask, can a place continue to function as a healthy community when the local people – especially the older and more vulnerable ones – have been priced out of living there? And is Órgiva being gentrified, in truth, as some claim? Let’s take a closer look…

Órgiva: 2005 to 2025

Twenty years ago, I’d landed in Órgiva with my young family, with no aim other than to try and escape northern Europe and figure out some way of making a living. Yep, I was one of those dreamers who thought a change of scenery would fix everything. Órgiva, back then, was hardly undiscovered, as some people might today imagine. Plenty of old hands made us new arrivals feel like the new kids on the block at the time, which we were.

What attracted us here? After all, Órgiva wasn’t exactly Shangri La. In his classic guidebook ‘Andalucía’, Michael Jacobs deems it hardly worthy of mention other than to say it is “resembles an Alpine town gone somewhat to seed.” Earlier visitors were no more enthused, with Gerald Brenan writing of his arrival there with dysentery in 1919 to discover that “Órgiva lies in deep mountain hollow, and its villages, half-hidden amongst orange groves and long-limbed olive trees are airless and shut in.” (‘South from Granada‘). And so he kept on moving.

But we loved it, and so we stayed. And Órgiva has also moved on since then. It might once have been a depressed former mining town battling depopulation and cultural stagnation, but an influx of mostly external influences has seen the town blossom into what it has become today. My memory of the Órgiva of 20 years ago is of a place that seemed to be struggling to evolve a new identity. Still very rural in many ways, it was a town of potholed roads, small shops and numerous bars and restaurants – all serving pretty much the same dishes. You’d be hard pressed to find anyone who didn’t call the place run-down, but it nevertheless had a charm and allure that was both genuine and unaffected.

There was a ragged lady with a kindly face, who sat most days on the main street tunelessly playing a flute. Like some kind of exotic bird, the trill of her instrument mingled with the caged songbirds in the open windows as the punctuated roar of youths on dirt bikes created a soundscape unique to Órgiva. And with mobile phones yet to truly catch on, shopkeepers still bellowed to one another across the street, while the clink of coffee cups outside Galindo’s café chimed harmoniously in the shadow of the church bells looming above. It was the smell of orange blossom mingled with diesel fumes; a friendly, hot, grimy place that was, at times ,ebullient, and at others as silent as the crypt.

There had been an influx of foreigners at the time, surfing in on a wave of cheap credit and intoxicated by dreams of a new life having watched TV shows and read Chris Stewart’s ‘Driving Over Lemons’. With fresh arrivals from The Netherlands, France, the UK, Scandinavia and Germany all the time, it made for an interesting mix of cultures as we attempted to settle into Alpujarran life alongside the – often bemused – locals. This tide of incomers retreated with the financial crisis, but there have been fresh waves since.

Cultural melting pot

These were the years of the legendary Dragonfest, and a steady stream of diggers, dreamers and ravers were making their way south and pitching up on Órgiva’s doorstep in places like Beneficio, Cigarrones and El Moreon. Add to the mix a sizeable population of followers of the mystical Islamic sect Sufism, as well as Tibetan Buddhists, permaculturists and New Age adherents, and there’s no doubt that Órgiva was and is something of a cultural melting pot. More recently, digital nomads have been turning up and finding a pleasant place to rest their laptops, with some 65 different nationalities now calling the town home.

Things were already looking up for the town even in 2005. True, there was no municipal swimming pool to cool off in, no football pitch for the kids to practice on, and no big supermarkets in which to do your weekly shop back then. The streets were less orderly and the traffic lights sometimes took the day off. No giant head of Don Quixote gazed down Calle Doctor Fleming, and no mysterious egg sculptures greeted new arrivals into town. But if one spoke with the ‘pioneers’ – those who arrived in the 1980s – things had already changed almost beyond recognition since the days when the town had dirt roads and no telephones.

Back to the 2000s and the arrival of Café Willendorf heralded the dawn of a more varied café scene, just as the opening of El Limonero, with its fusion of Spanish and international dishes, had tongues wagging that Órgiva had ‘arrived’ on the dining circuit. Since then, change has come thick and fast.

What changed in 2008?

But the financial crisis of 2008 to 2010 ushered in a new era of change for the town. With people struggling financially, and unemployment rife, a new – socialist – mayor was elected. She immediately put people to work, giving the town an emergency facelift. Graffiti was scrubbed from walls, broken pavements were fixed, and planters were filled with colourful flowers. I didn’t see any of this, at the time, as the economic situation had also hit us. I was forced to head back north, not returning again to Órgiva for five or six years. When I came back for the first time, I was surprised at the changes I saw. For the first time, Órgiva now looked like a more ‘normal’ Spanish town, as opposed to some curious throwback at the end of a long and winding road.

But, really, is Órgiva becoming gentrified?

Gentrification is an ugly, technocratic word. It sounds like a contraction of ‘gentle electrification’ – a kind of electro-shock therapy administered to savages to turn them into gentlemen. But rest assured, this strange process of cultural whitewashing tends only to happen to urban neighbourhoods in big cities – places such as London’s Hoxton, and Harlem in New York – rather than to small and quirky communities in the Spanish sierras.

What generally happens is that waves of young urbanites move into edgy yet affordable city areas, pushing up rents and attracting entrepreneurs who, in turn, set up the kind of businesses that attract 20 and 30-somethings with their healthy disposable incomes. Speculators pile in and, before you know it, property price increases have made the neighbourhood unaffordable for the urban poor who once lived there. Meanwhile, local government is happily sitting on a huge pile of cash raised from property taxes.

But Órgiva isn’t Oakland, and the concept of gentrification does not apply here. For a start, there is no big financial district, well-funded arts hub, or other lucrative source of income to attract incomers. True, they are reopening some of the old mineworks, but I don’t think that qualifies. Secondly, it appears that Órgiva has reached some sort of escape velocity when it comes to possessing a sense of cultural autonomy and economic independence. Businesses are small and agile, and people are – on the whole – resilient and autonomous. They are creative and tough-minded and mistrustful of big corporations. If Starbucks tried to open a branch, Órgivans would surely tell them where to stick it.

A new sense of civic pride

Furthermore, property speculation simply doesn’t work in Órgiva. In the past, the sight of people rifling through wheelie bins, surrounded by feral cats and mangy dogs, must have put off many a property speculator from out of town. One can imagine their sense of horror, of throwing the Merc into reverse and racing back to the ‘costas’ as Órgiva retreats in the rear-view mirror. For this, we can thank the less fortunate town denizens in preventing the kind of runaway property prices seen in other regions over the last couple of decades (please see market reports.)

These days, of course, the pavements of Órgiva are kept much cleaner than ever before. Well, the main ones, at least. Self-organised litter picking patrols sometimes deploy themselves in peripheral areas and dry riverbeds. Nothing much larger than a rollup filter escapes their attention. That said, you don’t have to stay too long to notice there are still problems. In particular, drug and alcohol addiction, and its associated issues – such as the occasional act of public disorder.

Being an end-of-the-line kind of place, Órgiva attracts drifters and people with not much to lose. This has led to a serious uptick in begging and petty crime, with locals saying that cars have been broken into, bicycles stolen, and items taken from in and around houses (especially those down nearby rural tracks). The town hall and Guardia Civil takes this seriously, and a crackdown is ongoing, although targeting motorists seems to be one of their main strategies.

The conclusion

Is this gentrification? No, it’s far simpler than that. Perhaps it’s something closer to a renaissance of civic pride. A few months ago, I allowed my dog to drink from a water fountain near the school and found myself being sternly rebuked by an elderly gentleman who seemed to have taken on the self-appointed role of ‘fuente’ guardian. This would likely not have happened 20 years ago. But in this instance I was in the wrong, and I knew it – fountains are for people to drink from, not dogs. ‘Lo siento’, lesson learned.

A new sense of self-esteem has arisen in the good people of Órgiva. You can see it in the manicured exercise areas, the even pavements, the freshly painted houses, the restored fountains and even the idiosyncratic art that adorns walls previously covered in graffiti and peeling posters. The town scrubs up well. Call it community spirit, or hometown pride, or civic self-regard – but don’t call it gentrification. And that’s not a baaad thing at all.

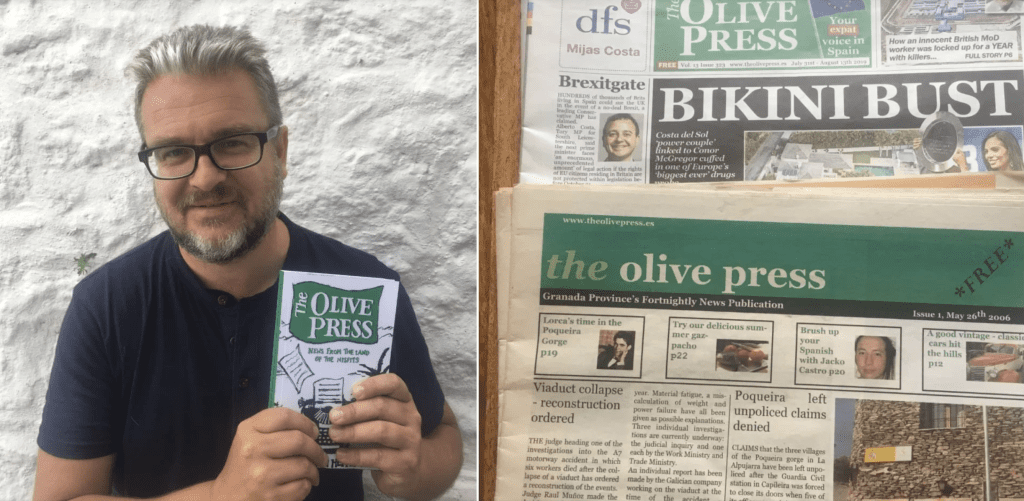

Jason Heppenstall is a writer who, in 2006, founded the popular newspaper, ‘The Olive Press’. His book, ‘The Olive Press: News from the Land of the Misfits’, is an offbeat story about life in Órgiva and has garnered glowing reviews – mainly for the funny bits.